Every fortnight (or so we hope) we feature a seagrass meadow from around the world. This week, Rosemary Mc Closkey writes about her field site in Porth Dinllaen in North Wales. Rosemary is currently a Masters student at Swansea University and she is studying juvenile fish populations in Zostera marina meadows.

——————————————————————-

Photos and text by Rosemary Mc Closkey

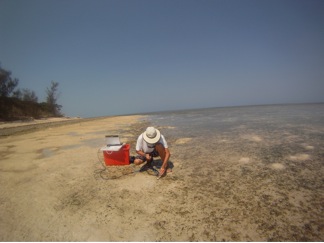

I am a student from Swansea University and I am currently undertaking a month of field work for my Master’s thesis, where I am studying juvenile fish populations in a Zostera marina seagrass meadow in Porth Dinllaen on the Llŷn peninsula, North Wales. My data collection has been carried out alongside and with the support of an on-going collaborative project between SEACAMS and the National Trust here in Wales.

I first visited the site with SEACAMS at the end of April this year to assist with their fish monitoring work and to assess some scarring of the bed caused by moorings in the bay. This also allowed me to get the ‘lay of the land’ so to speak, and to design the methodology for my project. I joined SEACAMS once more in June to carry out more work and to run trials on some small fish traps designed to catch shrimp and small fish. Unfortunately these yielded very little success and as I had yet to visit this site on the low spring tides, I was keen to return for an extended period so I could get a real feel for the site and to adjust my method. Myself and a field assistant returned to Porth Dinllaen at the start of August with a smaller, lighter seine net with a finer mesh than that which I had used with SEACAMS in April and June. These nets seem to be working successfully and selecting the age/size classes that I wanted.

My research thus far is focused on assessing sites of varying complexity and heterogeneity within the meadow in order to elucidate whether small-scale variations within the bed affects species assemblages. During the 1st week of August, low water on spring tide caused the bed to become exposed, thus allowing some assistants and myself to carry out a habitat assessment.

Plots of 36m2 were assessed and permanently marked out using marker pegs and GPS. Detailed photographs were also taken. I was initially skeptical as to whether or not the heavy duty orange pegs I had used to mark out the plots would last, but I was pleasantly surprised to see most of them have. They have proven very useful for relocating each plot. The main working hazard in that respect has been young kids stealing them for their sandcastles!

I have fished within each of the plots using an 8m beach seine net to assess the dominant species and size classes of juvenile fish. Initially I wasn’t sure whether I would catch the same species that were caught in the much larger seine net. I have found that I am catching all the same species as before, however the majority are juveniles, small fish and shrimps. The larger, fast moving finfish and bigger predators seem to evade the smaller net! The majority of the fish caught were wrasses, gobies, dragonets, sea scorpions, plaice, sticklebacks and pollack. We have also caught the slightly more elusive species such as little cuttlefish and pipefish.

I plan to stay one more week at this beautiful location to collect some more fishing data. Getting access to the site for this length of time has been a real joy and I have been very fortunate to be able to carry out extended field work of this nature for my masters project. I look forward to returning to Swansea in order to write up my results and my thesis.

For more information on The National Trust: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/

For more information on SEACAMS: http://www.swan.ac.uk/seacams/