Every fortnight we feature a seagrass meadow from around the world. This week, Elizabeth ‘Z’ Lacey writes about Akumal Bay, an ecosystem in the Caribbean off the coast of Mexico. Z is finishing her Ph.D. at Florida International University in Miami, Florida.

—————————————

Photos and text by Z Lacey

I have a confession. I did not go to Akumal Bay to study the seagrass beds; I went to study the coral reefs. Before you kick me off the World Seagrass Association blog, hear me out. I first came to Akumal Bay, Quintana Roo, Mexico to study the return of an important herbivore to the coral reef community BUT I was quickly and irreversibly intrigued by the seagrass beds and the graceful green sea turtles in short order. Does that redeem me in your eyes, fellow seagrass lovers?

But I get ahead of myself. Let me introduce you to a beautiful place that I’ve been working in for the past four years. Akumal Bay is located along the MesoAmerican Reef on the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico and its name means ‘place of the turtles’ in Mayan. It is a unique environment as it’s one of the few public access beaches for locals as well as serves the surrounding tourist populations coming from Playa del Carmen, Tulum and Cancun. There are lots of interested stakeholders, which is a challenge for the managers of this important ecosystem. Incredibly this bay is monitored by the non-governmental organization Centro Ecologico Akumal (www.ceakumal.org) and Director Paul Sanchez-Navarro. They rely heavily on donations and volunteer stewards to monitor the coral reefs, water quality and abundant turtle population. To do this they hold turtle walks, give informative lectures in the education center, run a recycling program, provide life jackets/snorkeling vests and many other initiatives, all free of charge to visitors and the residents of the nearby pueblos.

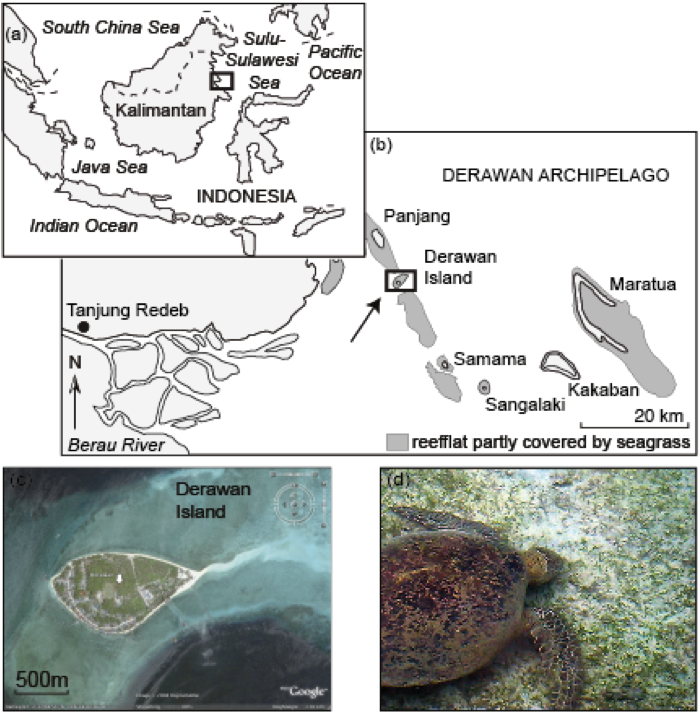

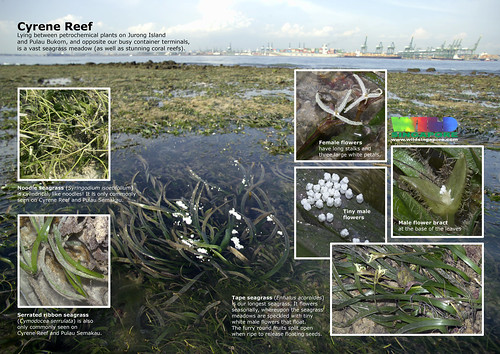

Unlike Siti’s last post on the diversity of species to be found in South Sulawesi, the seagrass meadows in Akumal typically consist of just three seagrasses: Thalassia testudinum, Syringodium filiforme and sparse Halodule wrightii intermixed with calcareous green macroalgae. The seagrass beds are patchy throughout the lagoon from the shoreline to the reef approximately 250 meters offshore. In some areas of the bay, patch reefs are interspersed throughout the seagrass meadow, providing refuge for fish, urchins and other diverse marine life.

Akumal Bay is easily accessible by tourists groups from land as well as those entering on boats via the channel through the adjacent barrier reef. Part of my research is considering this impact by humans on the seagrass beds and how the herbivores, both sea turtles and fish, have shaped this ecosystem. Similar to other regions along the Mayan Riviera, this area is experiencing dramatic population growth and even further tourism development. While the fate of these seagrass beds is unknown, change is inevitable. CEA is in a difficult position as they try to protect the ecosystem with their limited financial resources while also listening to the needs of the local residents, tour operators and businesses, which rely on the bay mainly for tourism income rather than as a food source.

Volunteers come from all around the world for a three month adventure at CEA and learn skills such as coral reef identification and sea turtle tracking. Throughout the years I’ve had volunteers from France, Netherlands, Germany, the Philippines and of course Mexico as they assist in my research along with their other volunteer duties. For some, such as my new friend Yvonne Kleinschmidt pictured here, they were completely unaware of the different types of seagrass before I took them into the field to make them honorary seagrass rangers. It’s been fun for me to teach workshops on identifying seagrass and macroalgae to the volunteers as part of their reef monitoring training.

Before you think it’s all work and no play in Akumal, I have to mention the many Mayan ruins to explore, cenotes to swim in and cities like Playa del Carmen to visit! Not to mention the amazing local cuisine and fresh fruits and veggies available at the farmer’s market in the town square. A day off from the field is rich in cultural experiences as well as ecological discovery – another reason I’ve come back to Akumal year after year. And while I initially studied the coral reefs, you can see how the interesting marine life living within the seagrass beds and the stories waiting to be explored were able to pull me into Akumal Bay!